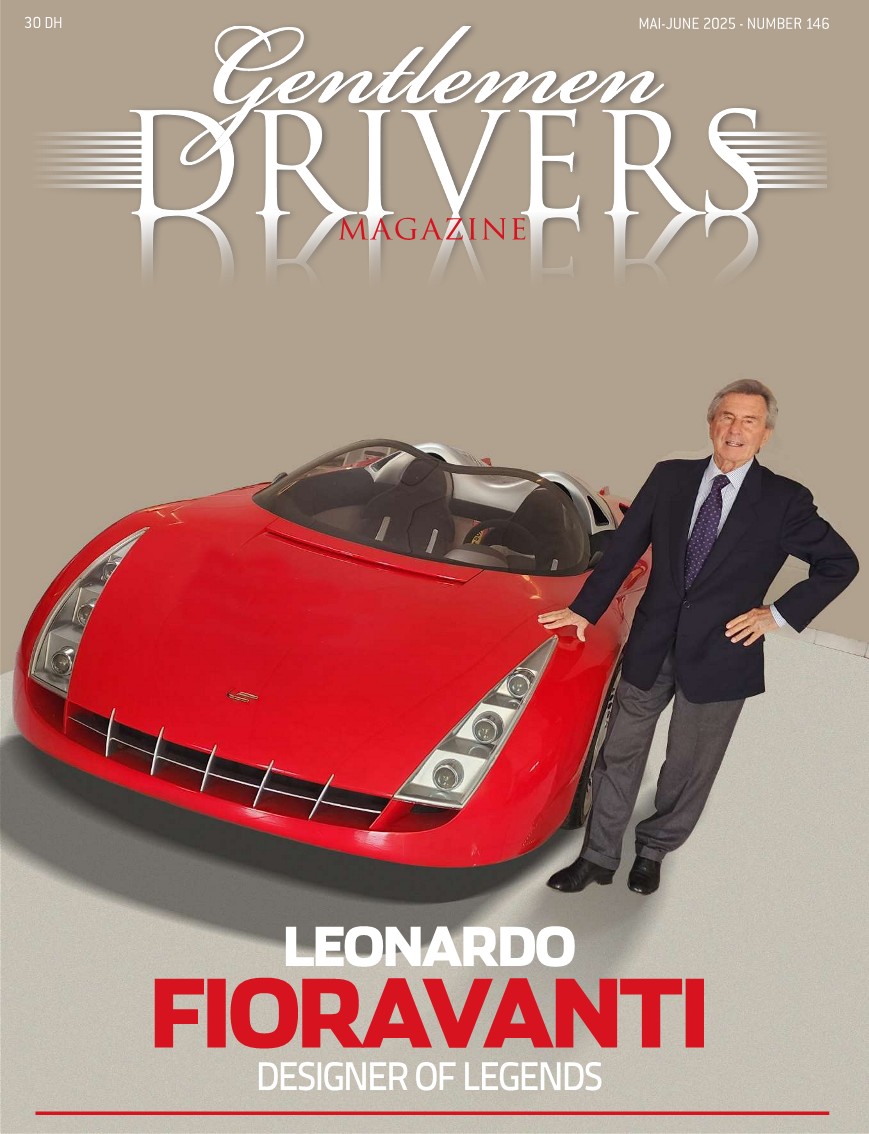

Supercar designer

In the annals of Ferrari design, many designers have etched their names in legend. But of all of them, one name has a particular resonance with fans of the marque: Leonardo Fioravanti. And for good reason: he is the designer behind some of Ferrari’s most iconic road cars. These include the Ferrari 365 GTB, better known as the Daytona, the Dino, the 512 Berlinetta Boxer, the 308 GTB, the 288 GTO, the Testarossa and, of course, the F40.

In this interview with Gentlemen Drivers Magazine, this exceptional designer looks back at the early days of his passion for design and his exceptional career at Pininfarina.

Discovering the captivating story in PDF

When did you discover your vocation as a car designer?

I started at primary school. I still have my third-year notebook with my name on the cover, along with the Savoie coat of arms. I started drawing at the age of seven and won a drawing competition. We were presented with an object on the desk and had to reproduce it. I finished before everyone else, so much so that they thought I’d cheated by photographing it.

Between the ages of 8 and 10, my passion turned to means of transport in general: cars, boats, airplanes… In my bedroom, I drew non-stop, much to the annoyance of my parents, who would catch me doodling instead of studying. Sometimes they’d yell at me to get rid of my drawings. In my book, I even published a sketch in which my father had written: ‘This is how you study, damn it!’

But despite their anger, they kept everything. When Pininfarina called me, my parents gave me three boxes full of my drawings. They realized that there was something serious about them. My approach to design has always been instinctive: I thought of a shape, I drew it, and, to my great surprise, the result corresponded quite well to what I had imagined.

How did you develop an interest in motor racing?

My father owned a Fiat 1100B Bauletto and a Topolino. In those days, children had to learn to play the piano. So did I, except that I practiced using the pedals as if they were those of a car: clutch, accelerator…

The Topolino had a key that looked like a nail. One day, I stole the key from my father while he was asleep and drove around the block. When my father offered to teach me to drive, he was astonished: Blimey, but you already know how to drive!’

Then, while studying engineering at the Ecole Polytechnique, I discovered the coefficient of friction and the influence of the contact surface on grip. This led me to test the grip limit of my tires on a round square near my home, at night. I realized that as the tires wore, the contact patch increased and improved handling in dry conditions. With some friends, we pooled our savings to take part in races with a prepared Fiat 500, then an 1100 TV. One day, at a race at Monza, I finished second. My father heard about it from some journalist friends who said to him: ‘Did you know that your son came second?

I was racing in secret, but he finally understood and simply said: ‘Go on, but be careful.» Later on, I drove Alfa Romeos and then, at the height of the Ferrari, I raced the F40, a car that’s difficult to master because of the turbo lag time that makes it temperamental.

You were close to Enzo Ferrari. What was he like?

I was lucky enough to know him well. I designed my first Ferrari at Pininfarina in 1964: the 250 LM Speciale. The model was a commercial success. Ferrari was delighted but wanted to know who this “young engineer from Milan” was. He learned my name when he discovered that the customers who had bought the car were going faster than the official Ferraris. Ferrari was skeptical about the mid-engine for the road, but with the success of the Lamborghini Miura, we set up a secret project at Pininfarina to convince him. We presented him with the Dino, and although he wasn’t totally convinced by the first prototype, he ended up approving the project. The Daytona marked a turning point. Enzo Ferrari immediately ordered a full-scale model, a rare decision.

He was a tough guy, a man of few words. After a few years, we became close and he called me directly: « Fioravanti, I want a Ferrari to go to La Scala with friends, four comfortable seats. Invent it as soon as possible ». Then one day, Vittorio Ghidella, an engineer at Ferrari, called me and told me that I would become the CEO of Ferrari. I left Pininfarina.

Talking of the LM 250, this was your first project on a Ferrari. What was it like for you?

Yes, it was in 1966. It was a small project for an American customer that nobody wanted to follow up. ‘Let the boy do it,’ they said. During the track test, my car ran faster than the others thanks to certain aerodynamic measures. At the finish, I was ahead of the other Ferraris. The Commander didn’t take it very well: ‘That little engineer from Milan dared to beat me, but at least he made me a lot of money’.

What does the F40 mean to you?

The F40 was exciting, but complicated. Because of turbo, there was a delay between the acceleration and the build-up of power. One day, testing an F40 on the roads around Maranello, I nearly missed a bridge! Despite this gap, it’s an infernal machine. Even today, many journalists who test supercars say that the F40 is still the most fun and exciting. I remember testing the first Evo models at Fiorano: when I got into first gear, the acceleration was so brutal that I changed gear without wanting to. Compared to a GTO, it was a missile!

Would Ferrari have been the same without Pininfarina?

Before Pininfarina, Ferrari worked with other coachbuilders, but the models were not always harmonious. When Pininfarina designed the first Ferrari, it wasn’t a revolution, but a fluid, pure line that has survived the decades. He had a unique ability to purify forms.

Enzo Ferrari couldn’t draw, but he had an exceptional eye. He would touch the bodywork with his eyes closed to detect defects. On one occasion, on the eve of a motor show, he had a windscreen redone because it was deemed imperfect!

What do you remember about Sergio Pininfarina?

He was a great liberal with a vision for the future. It gave me the opportunity to express my talent for 24 years.

And how did it go at Fiat?

It was short. I had an office on the second floor of Mirafiori, next to that of the boss Giovanni Agnelli, for whom I had directed the project for a three-seater Ferrari, designed by Aldo Brovarone, which made it easier for him to get into the cockpit because he had a problem with his leg, destroyed years before in a car accident. My imitations of his voice startled all the managers. As for the rest, I was a stranger to the gang and group logic that governed Fiat. Agnelli was an innovator. He wanted to make my Sensiva model, an electric car designed in 1993 and presented at the Turin Motor Show, but it was too advanced for its time. I left and founded Fioravanti, a design and engineering company.

What’s your take on electric mobility?

I’ve been interested in innovation since I was a child. It’s not easy to stop inventing and try to solve problems with the courage of simplicity. That’s why, unlike many others, I embraced the electric revolution. The first car in history was designed to be electric. My first drawings as a child were of electric cars. I don’t like the new Ferraris very much, they’re too bulky. But the problem isn’t the engine, it’s the aesthetics.

You have filed a patent for the design of a low-cost electric car….

Yes, I have been working on a system that uses the force of gravity to produce energy. You can do it in a car on the road, or on the sea with ships. I’m imagining two-lane motorways: one creating energy as cars pass by, the other recharging the batteries.

At 86, what keeps you working?

Anyone who encourages young people to follow their dreams is lying. In life, we only have the chance to achieve one thing. To young people, I say: set yourself a goal and persevere. I’ve been doing it for 86 years, which is why I can’t stop: I have to make my dream come true.

What does your day look like?

I wake up at 8 o’clock, go to the office, to Moncalieri, to Fioravanti, read my e-mails and work. I’m the only one left in the company. We’re no longer in the golden age of car design. In the afternoons, I write articles for magazines dedicated to Ferrari enthusiasts and I receive guests in my house on the hill. We all live here on the hill: me, Giugiaro, Spada, Ramacciotti. In the 60s, we all came here because Agnelli had chosen to live in the area, and I even produced wine.

Biography:

1938: born in Milan, Italy

1960: Graduates in mechanical engineering from Milan Polytechnic

1964: joins Pininfarina as a designer

1987: founds his own architecture and design firm, Fioravanti

1988: Enzo Ferrari recruits him as Deputy Managing Director of Ferrari, then Managing Director of Ferrari Engineering

1989: becomes Director of Advanced Styling at the Group’s Centro Stile Fiat in 1990, and Director of Design at Alfa Romeo…